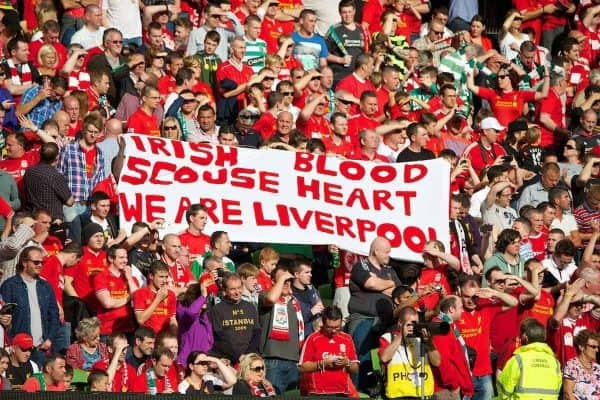

Not for the first time, Liverpool and Celtic face each other in a charity match, and with input from a few familiar faces, Sam Millne took a deep look into the historic connection between the clubs which goes further than football.

Hail batters the windscreen as the bus ploughs on through the darkness of the M6 back down to Merseyside. It’s February 2020.

The passengers have been up since early morning, but the mood is buoyant having just seen Celtic sweep aside Kilmarnock 3-1.

To the jocular annoyance of the Evertonian on board, intermittent outbursts of Roberto Firmino‘s ditty accompany Celtic anthems, old and new, as the soundtrack to the journey home. Half-and-half scarves are acceptable today.

The 2019/20 season is to be the first one since 1988 in which Celtic and Liverpool have both won their respective leagues.

As we roll towards a traditional away day meeting point, The Rocket pub, members of the party wave brief goodbyes as they’ll meet again in less than 24 hours. This time though, it will be at Anfield for the arrival of West Ham.

The driver of said bus is Peter Carney, a lifelong Liverpool fan who survived Hillsborough.

He has followed Celtic since he was a boy. He said: “Celtic started as my Scottish team; everyone had one. I was born into a Catholic family so Celtic was hereditary to me. When they won the European Cup in 1967 it was massive. That team was one of the best in the world.

“The more I learned about Celtic, the better they were. Everything I got to know about them reinforced my love for the club.”

Contrasting beginnings

The clubs lie nearly 220 miles apart, are located in different countries and play in different leagues, yet there is something that brings together fans of Liverpool and Celtic.

Each had very different beginnings and upon first glance, the pairing seems unlikely.

Liverpool were founded by John Houlding, a businessman and member of the Orange Order, whereas Glasgow Celtic were born out of charity for Irish immigrants in the East End of Glasgow. Liverpool FC’s link to the Orange Order was never really sustained and Merseyside clubs have become irreligious.

The same can’t be said in Glasgow. A lot of the younger generation of Celtic supporters identify as Catholic but don’t particularly follow the Christian religion. Although belief in God is definitely waning, a sense of belonging and everything that comes with Irish Catholicism can be what draws the younger generation.

Countless intertwining factors have come together to culminate in the relationship present today, however, the roots of most of them are entrenched in the cities’ ports.

The 33rd county

As a result of deep poverty and the potato famine of 1845-1849, around one and a half million Irish, made up of both Catholics and Protestants, travelled to Liverpool.

Many went on to make the perilous journey to America, but it’s estimated that up to a quarter of them remained on Merseyside instead. Such a large volume stayed, it’s thought up to 75 percent of Liverpool’s population could have some form of Irish ancestry.

At the same time, the Irish proletariat was also flocking to the west coast of Scotland, with many of them taking up residence in Glasgow. Ghetto-like areas came about and sectarianism started to kick off in both cities.

By percentage, the Archdiocese of Liverpool is the by far the most Catholic part of England, Scotland or Wales, even dwarfing Glasgow’s numbers. It’s only a small part of it, but the strong Irish Catholic presence on Merseyside has fed into the disdain that some right-winger factions seem to have for Liverpool.

The older generation can still remember sectarianist incidents in Liverpool. Margaret Millne comes from a Catholic family and lived in the city centre after the Second World War. She said: “There were always things going on. The Orange Lodge used to throw stones up at St Patrick’s church.”

On July 12, an Ulster protestant celebration day, things would often rise to a crescendo, “My grandmother would tell me I wasn’t allowed out on the 12th,” Mrs Millne added.

As time went by, the lines between Catholic and Protestant areas of both cities became blurred, and by the mid-50s sectarianism was dying down for good in Liverpool, largely down to post-war planning decisions.

In Glasgow though, sectarianism is still rife in the 21st century.

Politically on the same page

The clearing of Liverpool’s inner-city slums led to the displacement of communities. When people arrived at their new homes, they had been deliberately placed among one another, Catholic and Protestant.

Through being forced to co-exist, the hostilities eventually came to an end.

Instead of identifying as one religion or another, people now started to feel civic pride more intensely.

They were red or blue, not Catholic or Protestant.

The pressing issue was no longer of sectarianism, but rather growing social inequality.

Years of decline, culminating under Thatcher’s government, transformed Merseyside from what was once a mixed political area, into one of the biggest left-wing hotbeds in the whole of Europe.

Most of Glasgow, especially in the green and white half, feels similarly. The Celtic Football Club is an embodiment of the Irish Glaswegian community, which has long been on the wrong end of British imperialism throughout history. This, alongside Glasgow’s working-class background, has sent the Bhoys to the left also.

Although it may manifest itself in different ways, the sentiment today is just as vehement as in the 1980s, and there are regularly anti-Conservative banners held up on The Kop at Anfield or by the Green Brigade at Parkhead.

On numerous occasions, the two sets of supporters have felt isolated, particularly around Hillsborough and systems of government.

Many Liverpudlians don’t necessarily identify with ‘Englishness’ and the London-centric state. In 1999, Glaswegian activist, Margaret Simey, even said: “The magic of Liverpool is that it isn’t England.”

It’s a tendency shared by those who are cynical of the establishment.

When Labour’s long-established ‘red wall’ fell in the 2019 General Election, it only added to the detachment. The North’s major cities still voted Labour, but they were surrounded by a sea of blue that flooded former mill towns and mining communities.

The aforementioned, Peter Carney, remembers the first time he went to Celtic Park, a day which encapsulated working-class life in Glasgow and Liverpool at the time.

Carney recalled: “The first time I saw them live was in 1981. I went to Glasgow for an unemployment march and went from the march to the match on the bus. The bus was genuinely rocking all the way to the ground.

“It was against Rangers and I got a ticket outside. When I got in the ground it was saintly and strange. The noise and passion were incredible.

“Celtic were 1-0 down at half-time when he had to leave to catch the train back to Liverpool. When we got back to Lime Street, I learned Celtic had come back to win 3-1.

“When I think back to that day, I laugh at the thought of being in two 50,000-strong crowds; one taking on the Tories and the other taking on Rangers.”

Footballing friends

Celtic and Liverpool’s connection isn’t solely political, though.

Several players and managers have a place in their hearts for the corresponding club, and Liverpool’s Scottish connection goes back a long way. The Reds’ past is littered with great Scots of Rangers and Celtic persuasions.

From Billy Liddell through to Andy Robertson, they seem to fit in with the community ethos of the city and its clubs.

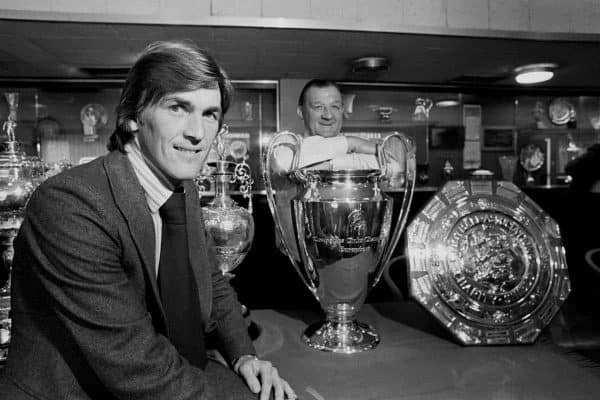

Bill Shankly and Jock Stein, the men behind the clubs’ rise to international fame, were good friends. Both worked in coal mines before they got their break into the football world.

The words Shankly allegedly said to his friend in the changing room after Stein had won the European Cup, have gone down in Celtic legend: “John, you’re immortal now.”

Stein just laughed, but the Liverpool manager was right; he was immortal in the minds of Hoops supporters.

The two of them along with the great Matt Busby, who played for Liverpool and managed Man United, all came from a Lanarkshire mining background. They instilled similar ethics into their teams, those of hard work and desire.

Shankly and Stein’s teams were built for the people. The latter’s 1967 European Cup-winning side consisted almost entirely of players from Glasgow.

A seminal moment

During Shankly’s tenure came a key moment that would be the catalyst for friendship between the clubs’ supporters.

Ian St John, born in Motherwell, scored the goal which won Liverpool their first-ever FA Cup in 1965 against Don Revie’s formidable Leeds. The trophy success meant that the Reds qualified for the next season’s Cup Winners’ Cup.

Liverpool had beaten Standard Liege, Budapest Honvéd and a strong Juventus team to reach the semis. They would be facing Celtic for the first time in the club’s history. A solitary home goal, scored by the legendary outside left, Bobby Lennox, left Shankly’s side with work to do in the return leg at Anfield.

Five days later, Tommy Smith and Geoff Strong were the scorers as Liverpool overturned the one-goal deficit but the night was marred by crowd trouble amongst a section of the travelling Celtic contingent.

Beer bottles were brought into the stadium and thrown towards the pitch, forcing Liverpool keeper Tommy Lawrence to move to the edge of his penalty area. One of the flying glass bottles hit a young Liverpool fan who was standing in the front row. He was badly injured.

Liverpool would go on to play Borussia Dortmund in their first European final and as fate would have it, the decider was up at Hampden Park in Glasgow. This provided the perfect opportunity for Celtic supporters to repent to their visitors.

That night, the relationship between the sets of fans changed forever.

Crucial member of the Hillsborough Independent Panel, Prof. Phil Scraton, who views Celtic as his second club and once turned down an OBE, was fresh out of the seminary and witnessed the Glaswegians’ hospitality first-hand. He remembered: “I said to my mum I was going to go to the final and she said: ‘You can’t do that; it’s going to be dreadful’. I was determined to do it.

“Before we went, Celtic fans had been writing to the [Liverpool] Echo and the club to say how sorry they were for what had happened. They wanted to make up for it.

“The various supporters clubs in Glasgow opened their doors to the Liverpool fans. The coaches got there early enough and were welcomed by Celtic supporters, then they laid on food and drinks. They were very generous. We didn’t have that much time by the time we got up there, but it was a real act of generosity.”

Liverpool lost the match with Reds captain Ron Yeats scoring an unfortunate own goal in extra time.

The Scotsman would go on to be the first of the six players or managers who would have their testimonial between Liverpool and Celtic. On the other hand, just two testimonials have been held between Rangers and Liverpool.

Scraton continued: “Coming back you could hear a pin drop. It was total silence because we were wet through and had lost. It was a lousy night.”

Earlier in the day though, a special bond had been formed.

“From that moment onwards, there was always a strong bond between Celtic and Liverpool. Anything in the past paled into insignificance. Every single moment afterwards, Celtic fans were fantastic,” the university professor added.

A new king

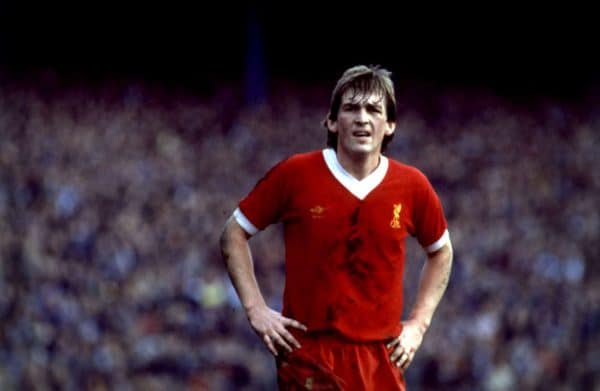

Later came Kenny Dalglish. He was brought up a Rangers fan but, once he had broken through into the Celtic first team, there was no looking back. He played over 200 times for the Hoops before Shankly’s successor, Bob Paisley, lured him to Anfield.

Liverpool had just won the European Cup, but Kevin Keegan had left for Hamburger SV and they needed a new talisman.

John Gribbon is a lifelong Celtic fan and described the impact of Dalglish’s move, saying: “He was probably my first boyhood idol; that leaves a mark on you throughout life.

“I remember the day Liverpool signed him and our neighbour told me. At first, I said I didn’t believe him then I said I was going to follow Liverpool. He told me that he was going to tell my dad and I told him I was only joking.

“I think I was seven at the time and I think a large section of the Celtic support, especially my age, share my view but not all. I know quite a few Celtic fans who prefer Man Utd and also some Everton to a lesser extent.

“My soft spot is for Liverpool and for me, the main reason is King Kenny.

“Dalglish is a huge part of the bond between the two clubs and cannot be underestimated in my opinion.”

John’s story is a familiar one in Glaswegian households.

There are quite a few of the older generation who prefer Man United to Liverpool. As well the club boasting an international pedigree, Manchester also has more Irish heritage than most places in England and, traditionally, shares analogous socialistic values with Glasgow.

In 1989, Dalglish was in his twelfth year at Liverpool. His playing credentials translated to the manager’s position and his team were flying high. Then Hillsborough happened.

Helping to heal

The media’s coverage of the disaster, aided by the authorities, added to the long list of sticks which were used to beat the reputation of Liverpool, a city already suffering from the false stereotyping of its occupants going mainstream and becoming normalised.

Whilst some of the country stared scornfully at Merseyside, it was neighbours Everton, then Celtic, who stood strongest by Liverpool’s side.

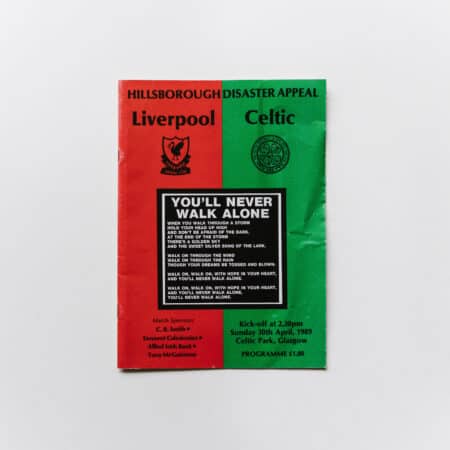

Fifteen days after the tragedy, Celtic hosted a friendly between themselves and Liverpool. The memorial match served to raise money for the families affected but it also showed solidarity with the Liverpool fans who were being blamed for the events in Sheffield.

Martin Donaldson is a Celtic fan with a Liverpool-supporting son. He was at Parkhead on April 30, 1989, and said: “I remember approaching the main stand that day and seeing so many different coloured scarves in the stadium as people from across the UK had come to pay their respects.

“On getting to our seats, we found we were sitting next to a group of family and friends who had made the trip up from Liverpool for the match. They were still raw with emotion but grateful for the welcome given by fans around them on their journey.

“Before the match kicked off, a Celtic fan laid flowers on the pitch at the Celtic end of the ground then fans held their scarves high and joined in a rendition of You’ll Never Walk Alone.

“Liverpool ran out 4-0 winners on the day, but the purpose of the match was not to test who was the better footballing side, but to allow a new chapter to begin as the healing process continued for the people of Liverpool.”

This has never and will never be forgotten by either set of supporters. To this day, at the memorial each year, there’s always a Celtic tribute laid out on the pitch with a contingent there from the Celtic supporters club. You’ll Never Walk Alone, which acts as the anthem of both clubs, really did have some meaning that day.

Celtic legend Tommy Burns, whose testimonial was against the Merseysiders also, tried to sum up the relationship between the people of Liverpool and Glasgow.

In 1989’s pre-match memorial programme, Burns said: “There are parallel lines to be drawn not only between the teams but also the cities we are proud to represent. Glasgow and Liverpool both have much in common. We both suffer from deprivation and the scourge of unemployment.”

He added: “The comparisons stand up to scrutiny for both the Glaswegians and Liverpudlians that have risen above that.

“They share a wit and friendliness that had formed a common bond. Both sets of supports are fanatical, the type whose lives revolve around football.”

The Celtic culture

There is a special spirituality and passion held by the fans for each club. This isn’t unique, of course.

Every football supporter feels a significant connection to their club, but there does exist a certain type of folklore surrounding both Celtic and Liverpool that is hard to find elsewhere.

Celtic Park and Anfield are both glorified as two of the best atmospheres in Europe, especially on European nights.

In 2018, renowned commentator Clive Tyldesley told Off the Ball that European fixtures at Celtic Park and Anfield were different to elsewhere: “I think there are certain atmospheres abroad that are just different.

“You’ll have experienced different nights in Turkey and in Greece, and it’s just different. But Celtic Park and Anfield on European nights take a little bit of beating, they really do.

“Within the stadium, Liverpool has almost a melodrama for a big game at Anfield. The incredible banners on the Kop; it makes you wonder how many hours and days people have spent on them. There is that sense of occasion at Celtic Park and Anfield which almost demands a show; put on a show for us, we’re putting on a show for you, you put on a show for us.”

The fan cultures encompassing each club, which form the basis for these emotional atmospheres, share similarities too.

Both like to be different, perhaps stemming from the anti-establishment nature of their supporters. They both see the past as something that can prop up the club’s future, not an obstacle to hold them back.

At different stages of the clubs’ history, they have been mocked for dwelling on bygone times too often.

Now, whilst they are in periods of on-field success, the customs of yesteryear that have been passed down on the terraces, only add to the aura surrounding the football clubs.

These outside perceptions propel the clubs forward on the pitch and off it, from a commercial point of view. When overseas supporters start following Celtic or Liverpool, they aren’t there just to watch the football. They are there to become part of a community and to buy into the culture around the football.

Our songs are different

Musical creativity with regard to terrace anthems is another one of the traits each set of supporters has in common.

This derives partly from a desire to dissociate from opposition fans who go to Celtic Park and sing songs of a sectarianist nature or those who visit Anfield and chant about poverty.

Every club has its devoted supporters who ensure their figurative songbook is kept alive, but the numbers listed are largely a collection of the same short tunes with different words, depending on the club you support.

At Liverpool and Celtic, it is different.

When a new player requires adoration, there has been resistance to go back to the same old tired old tunes.

In an increasingly Eurosceptic society, Liverpool look to Europe for inspiration. Songs like ‘Allez Allez Allez’ are usually started by young lads on European away trips.

Some of Celtic’s best recent conceptions include ‘I Wanna Be Edouard’, to the tune of The Stone Roses’ ‘I Wanna Be Adored’; and ‘Lustig You’re The One’, started well before England fans popularised the tune in football stadia.

Beside You’ll Never Walk Alone, ‘The Fields of Athenry’ is the other notable tune that the clubs share.

This is no coincidence.

The ballad, set during the Irish famine which triggered mass emigration, was adapted in 1996 by a Red named Gary Ferguson.

Fergo, who came up with the Liverpool version, said: “We played at Celtic, in I think a testimonial and it was getting belted out.

“I thought we should sing that without the religious undertones and one night I just had The Dubliners on and started to put words in for Liverpool.

“Bearing in mind that around 1995/96 Anfield was going through a patch in time when the atmosphere was, to be blunt, dreadful at times, I was hoping with the help of the lads, I could get it up and running.”

It did catch on and now Fields of Anfield Road is probably the most institutionalised song on the Kop after You’ll Never Walk Alone.

One of the more recent Anfield hymns is for Virgil Van Dijk. He is serenaded weekly to the tune of Dirty Old Town, a song considered Irish folk despite actually being about Salford.

Ewan MacColl, the writer of the ballad, was born in Manchester to Scottish parents and was a Labour activist.

Times change

Football and society evolve. On the all-standing Kop, occasional shouts of Celtic or Rangers would go back and forth between its dwellers.

Nowadays, you are far more likely to encounter an Irish tricolour on the Kop than a Union flag, which is a million miles from the ’70s when British flags were commonplace amongst Liverpool fans on European adventures.

If you were to display a flag of the Union or St George on an away day now, it would be profoundly frowned upon.

The bond between Liverpool and Celtic is different for everyone, especially with the ever-increasing globalisation of football.

Many even feel that there is no association between Celtic and Liverpool but there will always be mutual respect between the two, and scarves embroidered with the names of both clubs will continue to be sold.

Steven Gerrard‘s appointment as Rangers manager in 2018 was accepted on all fronts despite his Catholic ancestry, reflecting the more liberal approach society takes to religion.

There are plenty of Protestants who follow Celtic home and away. Dalglish and former captain Scott Brown, along with nearly half of Celtic’s great Lisbon Lions were born Protestant.

Andrew Murdoch is an ardent Celtic supporter who writes for Not The View, a prominent fanzine. He said: “While Celtic has very strong Catholic roots, the support is much more varied. I’m not Catholic and the guys I go to the games with for the past 30 years are probably majority Protestant, something we only discovered about two-three years after we had all met up!

“There are a variety of reasons for that. For me, who has a father who grew up in Ibrox, Dalglish was the deciding factor and once you’ve chosen, that’s it. My mates growing up were all blue, they accepted it, but their parents were less understanding.”

Others were kicking against the exclusionary employment policy at Ibrox – it took until 1989 for Rangers to sign a Catholic player, Mo Johnston.

There are still ongoing sectarian splits but gone are the days when Rangers would refuse to sign players because they heralded from a Catholic family.

Celtic and Liverpool football may only meet on the pitch once in a blue moon, but the common values of their supporters cross paths far more regularly.

You’ll Never Walk Alone.

This article was originally published in 2020, at The Football Pink.

Fan Comments