As ITV airs the emotional docu-drama, Anne, the story of Anne Williams’ heroic fight for truth and justice for her son, Kevin, who was unlawfully killed at Hillsborough in 1989, Jeff Goulding takes a look at the 1988/89 season in review in the first of a two-part series.

In April 1988, a horse named Rhyme and Reason won the Grand National at Aintree, in what was perhaps one of the universe’s most ironic of jokes, for Britain was a country that seemingly possessed neither quality.

For a record-breaking 3,164 days Margaret Thatcher had presided over mass unemployment, industrial strife and cuts to public services. Her government had discussed abandoning Liverpool to “managed decline” and was now drawing up plans to introduce a “Poll Tax,” with Scotland the testing bed just a year later ahead of a rollout across the entire United Kingdom. It would prove a policy gamble too far, and would thankfuklly ensure her demise two years later.

Liverpool, meanwhile, had continued in its time-honoured tradition of collecting the country’s footballing silverware and distributing it between Anfield and Goodison, with most of it ending up at Anfield.

I often think of Liverpool’s story during the 1980s as a tale of two cities. On the one hand there was the seemingly endless grind of being skint and desperately trying to find work, of scraping together enough cash to go the game, buy records and eat, in that order.

The fabric of the place seemed threadbare in parts, yet colourful and lustrous in others. It was home, filled with the bare necessities, while the luxuries of life could be found in football and music. They were heady days and contradictory times.

Politics and football

For many of us, the decade brought a political awakening. In 1988/89 I was dividing my life between football and politics. During the week, I would be helping to organise an “anti-poll tax union” on my housing estate, attending meetings where we discussed anything from Thatcher to Trotsky and read books on Marx and Lenin. At the weekends I went to the game or sat in pubs trying to make a few pints and a debate last all night. We protested, flyposted, petitioned and sold political papers, attended gigs and travelled the country supporting our team.

If I’m honest, for all the difficulties and struggles of daily life in the 80s, for me, there was joy in all of it. Through the prism of my Liverpool bubble, I believed I was living through an epoch of great change, a time in which ordinary kids like me were discussing high ideas and speculating on what kind of future we’d create “after the revolution.”

I was consumed with ideas of revolution back then. I still believe we need one now, I just thought it could actually happen in the 80s. I had no idea that the end of the decade would bring the curtain down forever on my youthful naivety, and that what I had always suspected to be true about the nature of politics and the state would be borne out before my very eyes, and that life would never be the same again.

Reigning champions

Liverpool FC began the 1988/89 season as League Champions, however, they had unexpectedly and spectacularly failed to secure a second League and FA Cup double after losing to Wimbledon in the 1988 FA Cup final. The so-called “Crazy Gang” won the match by a solitary goal, and in a moment that will likely haunt John Aldridge to his dying day, the Reds missed a chance to level from the penalty spot.

As Anfield geared up for the new season and a renewed assault on the citadels of football, we were giving up the pound note and trading it for a coin. Nurses, Posties and Ferry workers were on strike, the Ford escort was flying off the production lines at Halewood and Dagenham. In Liverpool, the Albert Dock reopened and Britain got ready to “welcome” the US President, Ronald Reagan. Meanwhile, concertgoers had packed Wembley to demand the release of Nelson Mandela who was marking his 25th year in captivity.

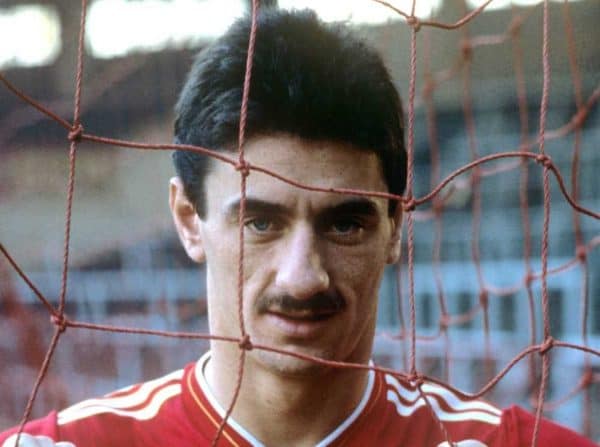

On the international football stage, English fans had been arrested in West Germany for hooliganism, while their team slumped to the bottom of their group. Back home Paul Gascoigne became the first £2m player, a record beaten shortly after when Everton paid £2.3m for a 22-year-old Tony Cottee. Not to be outdone, Liverpool took six weeks to smash the barrier again by shelling out £2.7m to bring Ian Rush back to Anfield from Juventus.

The outlay on Rush meant there was little left in the transfer kitty, and Kenny Dalglish would be far more frugal with the remainder of his deals, adding Nick Tanner from Bristol Rovers for £20,000 and David Burrows from WBA for £550k, while Barry Jones would arrive in January 1989 from Prescot Cables, for the princely sum of £500. The club would recoup some of their outlay by shipping out Nigel Spackman, Kevin MacDonald, John Durnin and Jim Beglin for a combined £800,000.

The Charity Shield, at Wembley on August 20th, 1988, presented the Reds with a chance to restore their dignity and pride and wreak revenge on Wimbledon. They would win the game, but not before another scare. John Fashanu put The Dons ahead after 17 minutes, but John Aldridge would at least partially make amends for penalty miss just four months earlier, by winning the game with a brace of goals.

Aldridge continued where he left off at Wembley, rattling in a hat-trick against Charlton on the opening day of the new season. The Reds were off and running, and none of us had any doubt that the magic would simply roll on for another year.

Next up was a seemingly meaningless encounter with Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest at Anfield in the Centenary Trophy Quarter Final. The competition had been established to celebrate 100 years of the Football League.

After scoring five goals in two games, Aldridge was dropped to the bench as Rush made his first start for the Reds since his return from Italy. Liverpool ran out 4-1 winners and although Rush was a constant menace in front of goal, he failed to hit the target. Instead, the goals were provided by Barry Venison, Jan Molby from the penalty spot, Ray Houghton and John Barnes.

A 1-0 away win over Manchester United in September brought some joy but the Reds followed that up with two frustrating 1-1 draws away to Aston Villa and at home to Tottenham. The latter was particularly galling as Liverpool had seemingly grabbed a game-winning goal with just 12 minutes remaining after Spurs had fought hard and created more than enough scares. However, joy on the Kop would be short-lived when the London club levelled just a minute later.

The game would also prove to be the last until January for Grobbelaar after the Reds’ keeper had contracted meningitis. Mike Hooper would deputise in the meantime and next up was a Centenary Trophy Semi-Final tie at Highbury, with Arsenal the opponents. Liverpool lost the tie 2-1, with their only goal scored by Irishman Steve Staunton who had only made his debut for the Reds three days earlier against Spurs.

Liverpool’s title defence was beginning to look a little shaky. Dogged by inconsistency and with their former goalscoring superstar Rush struggling to find the net they would find themselves eight points off the top spot in fourth place at the start of November.

Home form was especially baffling, having won one, drawn three and lost one. The Reds’ away form was marginally better and their three wins on the road prevented them from sliding into midtable.

Rush ends his drought

Throughout this spell, Liverpool had sought solace in the League Cup and Rush finally found the net after nine games without a goal, something that had been unthinkable during his first stint at Anfield. The moment came against Walsall in a game under the floodlights at Fellows Park in October.

The striker’s relief was obvious and so too was his manager’s, who felt that the goal might be an ominous sign for Liverpool’s opponents. The Times: “The burden of the search was beginning to weigh heavily on his slim shoulders, but the strike which finally broke his duck was straight out of his own goal poacher’s manual.

“Receiving the ball from MacDonald with his back to goal he held off his marker to turn and sweep the ball beyond Barber. The implications of that strike for the rest of the first division can easily be guessed.

“Even his manager, Kenny Dalglish, allowed himself a relaxed smile of appreciation. After making his obligatory statement that everybody had played well and he was always pleased to see anyone in a Liverpool shirt score, Dalglish added: “It won’t do him any harm, and it won’t do us any harm either.”

Rush was less diplomatic though and would refuse to talk to reporters after the game, accusing them of “slaughtering” him throughout his drought.

It perhaps illustrated just how much he had struggled and how alien leaving the field without a goal had felt to him. Sadly, he would net just 11 times in 32 games during the 88/89 season. It was a respectable return, however, when contrasted with the record of his Scouse counterpart, Aldridge, who bagged 31 goals in 47 appearances, the decision to part with Aldo in the September of 1989 seemed inexplicable to many of us.

Cup embarrassment

The win over Walsall had set up a clash with Arsenal at Anfield. John Barnes hit an opener but it had taken just six minutes for David Rocastle to level. In truth, it was the least the Gunners deserved. A goalless encounter in the replay at Highbury set up a second replay at Villa Park in November.

That month had seen the release of grim statistics on the HIV epidemic, revealing that up to 500,000 people in the UK were infected and 17,000 had tragically died from AIDS, the disease associated with the virus. Meanwhile, on the international scene, Polish Trade Unionists were fighting for freedom in Gdansk, receiving unlikely support from Margaret Thatcher, whose own record on the rights of unionised labour was questionable at best.

Around this time, many of us in England were protesting the Government’s ultimately failed attempts to introduce ID cards specifically designed for football supporters. We argued that we were being demonised and that our elected representatives had nothing but contempt for us. It turned out we were right.

At the end of the month, the Reds were unceremoniously dumped out of the League Cup in the fourth round with a 4-1 defeat to 19th-placed West Ham at Upton Park. This was Liverpool’s heaviest defeat in a cup competition since 1939 and the sense of embarrassment was acute.

A brace from Paul Ince and a strike from Tony Gale sandwiched a somewhat spectacular own goal from Steve Staunton. This how the Liverpool Echo saw the incident: “The youngster was perfectly placed on the edge of his penalty area to intercept a left wing cross from David Kelly and decided to turn it back to his goalkeeper. Unfortunately he caught the ball perfectly and sent in an effort Aldridge would have been proud of. Mike Hooper dived in desperation but the ball beat his grasp and rolled into the net off a post.”

The December football schedule was remarkably light by usual standards. The Reds played just four games that month, but their form could be described as lacklustre at best. 1-1 draws away to Arsenal and home to Everton opened the month in a somewhat miserable fashion, and just when we felt things couldn’t get any worse, Dalglish’s men served up a 1-0 home defeat to table-topping Norwich.

“Out of touch”

Liverpool’s big conundrum throughout the season had been whether to start with Rush or Aldridge.

The latter had received an award before the Norwich game for scoring 26 goals in the previous campaign, yet he would see out this game as an unused substitute. The man who took his place laboured for much of the match along with midfielders Houghton, Barnes and Beardsley. Only Ronnie Whelan looked like possessing the guile to conjure an unlikely breakthrough for the Reds.

The press declared that Rush was not the striker he once was, in truth the whole team could not be further removed from the swashbuckling side that had blown away all before them just a season earlier. The much-celebrated return of the Welsh hitman had so far not delivered the fuel injection many of us had imagined.

The press branded Liverpool “out of touch” and rival supporters sensed the final demise of Liverpool’s two decades of domination. Their prophecies would of course ultimately be proven correct, though they would have to wait a couple of years to see it.

This extract from the Times gives a revealing insight into how Fleet Street viewed the state of the game and Liverpool’s faltering title defence:

“Not so long ago teams went to Anfield in trepidation, hoping to learn from the experience but expecting to lose. That Norwich City not only avoided defeat there on Saturday but also strengthened their position at the top of the first division says much about their progress over the past 12 months.

“It also says much about the elitist attitude which pervades English football. Those who believe Norwich can add long-term consistency to their skill and a superb organizational sense, have been in the minority.

“This result will be viewed as another setback for the out-of-touch League champions and not the triumph for Norwich, both in actual and psychological terms, it undoubtedly was.”

In December the Health Minister, Edwina Curry, resigned after revealing that much of Britain’s egg production was infected with salmonella. Her comments had the expected impact on the country’s farming industry and her career was put into the deep freeze for a while. There were no tears shed for the Liverpool-born Conservative MP on Merseyside of course, but I remember thinking it both ironic and emblematic of the country at the time, that a Minister could be forced to resign for telling the truth.

Tragedy strikes

All that remained of a month most Reds would like to forget was a Boxing day trip to Derby County. In the run-up to the game, the news focussed on the horrific events in Lockerbie, a small town in Scotland. This tiny community was unwittingly thrust into the global psyche when Pan Am Flight 103 exploded in the skies above the town, killing 270 people. The dead included 259 passengers and crew and 11 people on the ground.

I remember feeling the horror of that event and struggling to imagine the terror such a huge tragedy would evoke in such a small population. I thought of the people involved, as we all will have done, and hoped their passing was so quick that they were oblivious to it. Then I got on with life and Christmas.

That’s what you do in the face of an unimaginable tragedy that’s happening somewhere else, isn’t it? When you’re not involved directly, you feel pity and sympathy. If there’s a way to show practical solidarity you do whatever you can, then you try to get on with the struggle of everyday existence. Months later, I would learn that it’s not so easy to do that when tragedy strikes much closer to home.

“Liverpool for the title”

Reds supporters made the trip to the Baseball Ground on Boxing Day and joined a crowd of just over 25,000 to take in the festive match. Liverpool faced two players who would one day line up at Anfield with a Liverbird on their chests, Mark Wright and Dean Saunders. Derby supporters would perhaps have looked at Liverpool’s form and dreamed of a late Christmas present of their own.

On Christmas Day, if they were lucky, kids would have woken up to such classic gifts as Nintendo games, Barbie Dolls, Micro-Machines or Pictionary. By now, I was too old for all that. If they were unlucky, they would have watched Cliff Richard’s Mistletoe and Wine revealed as the festive number one on Top of the Pops. I tried not to let that dampen my spirits too much.

Elsewhere on telly, the BBC had treated us to Santa Claus the Movie, Back to the Future, Silverado and perhaps appropriately, given Liverpool’s precarious title defence, the film Jagged Edge.

Liverpool were under huge pressure going into the tie against Derby. Their defeat to Norwich nine days earlier had seen them slump to sixth in the table. Their opponents had moved up to fourth and had only lost one game in nine. Liverpool had gone five without a win.

However, despite a spirited effort from the home side, Rush settled the game to send the Reds supporters home with a little Christmas cheer.

The victory had moved them up three places in the table and despite their obvious frailties and inconsistencies, many of the newspapers performed an about-face and declared the victory to be ominous for the rest of the league. The Guardian would go all out and round off its match report with the words, “Liverpool for the title.”

Such had been Liverpool’s dominance over the previous two decades, the football commentariat seemed unable to see past another glorious ending for the Reds come May 1989 and perhaps sensed they were about to go on another mammoth run to claim the title. After all, that’s what we had done so often.

I’m not sure how I felt back then, memory is a funny thing and hindsight bias is always a factor. I doubt I would have been too far behind the gentleman of the press though.

As 1988 drew to a close, I’d have still been blissfully dreaming of revolution on the streets and a glorious red triumph on the pitch come the end of the season. None of us had any clue of what lay in store, or that this would be for so many of us, a season without end.

Fan Comments