In the wake of Fenway Sports Group’s decision to furlough many of Liverpool’s non-playing staff using a government scheme, Jeff Goulding puts the club and its values under the microscope.

My initial response to a statement issued by Liverpool Football Club on Saturday, in which they declared that they would be paying staff 100 percent of their wages, while discussing wage reductions with players and carrying on activities in the community, was to welcome it.

To be honest, I was busy, only scanned what was a sufficiently woolly release for me to miss the central point: that they would be using the government’s furlough scheme to pay 80 percent of some workers’ wages, while topping up that up to 100 percent from their own coffers.

Once I realised this, it was hard not to share the anger of others and to escape the sense that Liverpool had become no different from the likes of Mike Ashley, Daniel Levy and Richard Branson; rich men who could easily afford to pay their workers during a crisis, but who instead chose to ask the government to do it.

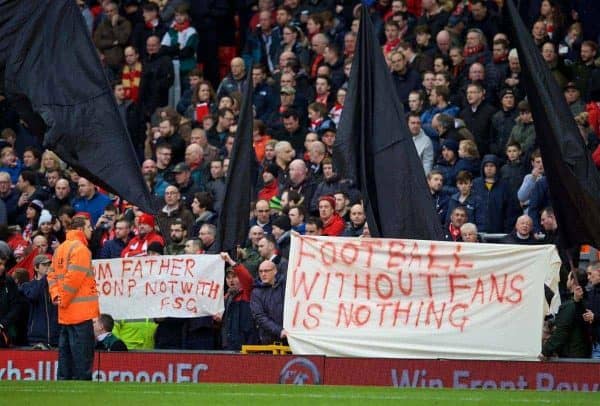

Such moves are rightly judged as examples of opportunism, and even profiting from a crisis. To see our club do it is jarring, especially when we have been constantly fed the line ‘We Are Liverpool. This Means More.’. The idea of the football club and its supporters as a family or community is one that appeals to our sensibilities, of course.

Liverpool as a city, at least in the last 50 years, has developed a broadly left-wing identity, as evidenced by the complete annihilation of the Conservative Party on the council, and the fact that all of its MPs represent the Labour Party. You can, of course, still find the odd working-class Tory in Liverpool today. The point is we know where they live and they tend to keep quiet.

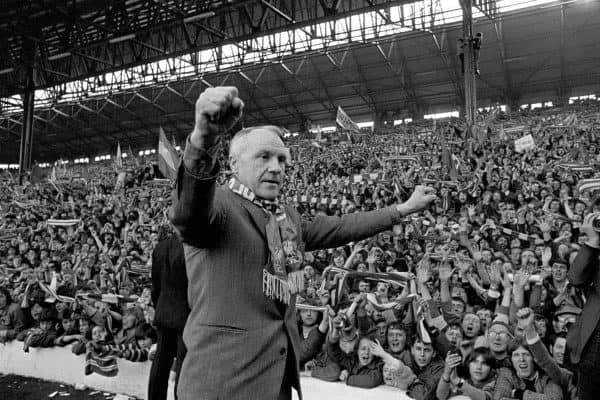

The owners of our football club are acutely aware of this, and clearly they have sought align their marketing strategies and corporate identity with ours. They’re helped in this by the club’s association with powerful socialist figures like Bill Shankly.

In the 1960s, Shankly rebuilt the footballing side of Liverpool FC using broadly socialist principles. He argued that the only way to achieve success was through collective effort and sharing out the rewards. He was right then, and I believe his principles hold true today. However, whenever he wanted a player, he would have to fight tooth and nail to persuade the men with the capital to part with some of it.

Liverpool Football Club was and still is a business, no matter what Peter Moore or anybody else suggests. In 2019, the club’s CEO said this: “The success of Liverpool Football Club is based on socialism. Bill Shankly, a Scottish socialist, built our foundations. Today too, when we speak about business questions, we ask ourselves: what would Shankly have done? What would Bill have said in this situation?”

Did Mr Moore believe this when he said it? Maybe. But it doesn’t surprise me that the socialist ideals of Shankly would have limited influence over the need to maintain profit and reduce costs.

In truth, what we have at best is an uneasy accommodation between the two philosophies at Liverpool. On the one hand we have the club’s very visible support for local foodbanks and charities, its vision and strategy to market the club as a family and appeal to the collectivist identity of its supporters. On the other, we have its unsuccessful attempts to monopolise the word ‘Liverpool’ and hike ticket prices to £77.

In each of those cases, the club stepped back from the precipice—not because of a conversion to Marxism or Corbynism, but because it would have hurt the business to proceed. They calculated that on balance it was better to take a short-term hit for a greater return later.

Many of the objections to the club’s most recent move have been based on this argument. People like Jamie Carragher have suggested, correctly, that using government subsidy destroys the goodwill built up as a result of Jurgen Klopp‘s obvious and genuine compassion and magnanimity in the wake of the suspension of the Premier League.

In other words, it hurts the image of the club and, by definition, the business.

Meanwhile, others are angered that the club has betrayed its values and rendered itself just another corporate entity driven by the profit motive. My fear is more along the lines that—despite the public facade—it always has been.

It is hard, even impossible to justify an organisation managing the level of turnover Liverpool does making use of government aid to pay any of its workers. At least it is if your principles are based on, as Shankly put it, “everybody working hard to achieve our goals, and everybody sharing in the rewards at the end of the day.” However, for those concerned mainly with maximising their capital, this clearly makes perfect sense.

Therein lies the dichotomy. Either a football club is a community asset run in the interests of its people, which is how many of us like to see ours, or it is a business run for profit. Can it really be both? I’m not sure it can. As long as it is the latter, we will continue to see these kinds of missteps. The club will always find itself clashing with the values of its supporters.

Does the latest controversy make me angry? Well, yes. But I am in no way surprised by it. For that to be the case, I would have had to expect something different in the first place. I would have had to have believed the idea that my club was being run by socialists. I never have. Why would I when my experience has taught me the opposite?

Why would we need groups like Spirit of Shankly to defend our interests, if our club was a community cooperative? Why would David Moores have sold it to a couple of hucksters straight out of the 1980s ‘greed is good’ paradigm if he wasn’t primarily driven by getting the best return on his investment? And why would the club attempt to monopolise the name of our city if it was solely driven by the interests of the community? You see my point?

I’ve always been realistic about what motivates the ownership of our club, and am fairly sure it’s not the common ownership of the means of production distribution and exchange. I, on the other hand, see our club very differently. I believe it should belong to its people and be run in their interests. If that is ever to be achieved, we have to understand that there is a fundamental difference between the two models and a mixture of the two is doomed to failure.

People are right to be angry at the club and to voice that anger as they see fit. But we should also be seeing the bigger picture and the inherent contradictions being opened up everywhere by this pandemic. The virus has done more to expose what’s wrong with the way our lives and economies have been run than any political movement in my lifetime. There is no sphere of life that isn’t touched by it, and no glaring inadequacy left hidden. COVID-19 has challenged so many long-held assumptions that it’s becoming hard to keep up.

Only months ago we were being told by our politicians that there was such a thing as “low-value people” and that anyone earning less than £25k a year was unskilled and therefore undesirable. Today, we can’t live without these people. We were led to believe that the market could solve all our problems and was more efficient than state intervention. Today, the government is having to intervene on a scale that Lenin would have been proud of. Well, almost.

We were also once assured that there was no magic money tree. Not only has one now been located, its fruits appear to be plentiful.

And in football we are seeing more than ever before that the business is not run in the interests of the people, but in the interests of sponsors, advertisers and broadcasters, because it is they who pay the bills. It may still be a beautiful game—it really must be given how much I miss it—but it definitely does not belong to us. It should, but it doesn’t.

However, by venting our rage solely on the mismanagement of football, we may be helping out those who would rather we were looking elsewhere right now. Anywhere but at the glaring deficiencies of the people running our country. The people who, despite having a head start on other countries, delayed and dallied, while flirting with disastrous ideas like ‘herd immunity’. The people who have cut our public services to the bone, leaving absolutely no slack in the system capable of dealing with this public health emergency.

When Matt Hancock aimed both barrels at Premier League footballers recently, accusing them of not showing leadership, I believe that’s exactly what he was trying to do. Distract us, shift the blame and the focus. Yet his party’s ideology has always been based on self-enrichment and to hell with the rest. I am yet to see a cabinet minister take a voluntary pay cut or the owners of Fortune 500 companies being told to show some leadership.

It’s interesting that with the current furore over LFC’s furlough faux pas, few of us are focusing our attention on this form of rank governmental hypocrisy. Of course, I am not advancing conspiracy theories here, just suggesting that all of this is undoubtedly convenient for Hancock and his ilk.

Meanwhile for the furloughed workers at Anfield, there will doubtless be relief that they will receive 100 percent of their wage and not the 80 percent their Spurs counterparts will get. That remains the bottom line, no matter how poorly the club have acted in this matter. It is to be hoped that, just as they have previously with other misjudgements, they will move quickly to put it right.

If there is to be any positive legacy at the end of this public health nightmare, then it has to be that there can be no return to the status quo. Everything must now be questioned, and where necessary things have to change.

That is as true about about the government, the economy and society in general as it is about football.

Fan Comments