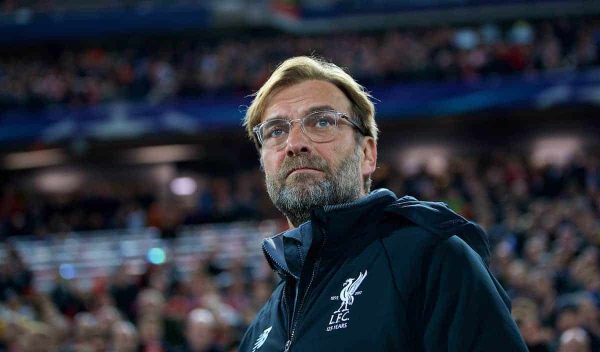

Jurgen Klopp has proved his ability to influence Liverpool’s form with system changes, and Richard Jolly believes this should come more often.

Sometimes imports become more English than the English. Jan Molby started speaking with a Scouse accent. Didi Hamann became a cricket fan. Jurgen Klopp played 4-4-2.

Or he did at West Ham anyway. It may be a one-off or a sign of things to come. It worked, albeit against a shambolic side who were ushering Slaven Bilic towards the exit.

Few think it represents Klopp’s ideal system – like most who value possession, he has a preference for at least three players in the centre of midfield, even if there is the possibility for the nominal wide men to cut in and form an advanced pair ahead of a deeper-lying duo – but the interesting element is twofold: firstly, that he even thought of it; and secondly, that Liverpool executed those plans so well.

There was a time in spring when Liverpool seemed sterile playing the 4-3-3 that had been so dynamic earlier last season. Klopp proved more flexible than his critics recognised.

He switched to a diamond midfield with two strikers – the Plan B that had brought the December 2015 6-1 thrashing of Southampton – at West Ham in May. He occasionally sought to see out games last season by introducing a third centre-back.

If the traditional, straitjacketed English 4-4-2 seemed a stretch too far for a manager whose tactics, with such narrowness in midfield and attack, and such fast, fluid interchanging of positions, appeared revolutionary and revelatory, there was a Kloppian twist.

When Liverpool had the ball, when they surged forward, it was more like 2-4-4, an effective way of getting behind opposing wing-backs.

Yet had another manager configured the same players in a 4-4-2, there may have been little surprise. Mohamed Salah excelled as a No. 10, an unfamiliar role to English audiences, but everyone else occupied either their preferred position or one where they have often appeared.

Liverpool have barely played with width, other than that supplied by full-backs, in Klopp’s reign. Yet in Salah, Sadio Mane, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and James Milner, they have four players equipped to play much nearer the touchline.

Adaptability

![LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND - Tuesday, September 12, 2017: Liverpool's manager Jürgen Klopp and assistant manager Zeljko Buvac [L] during a training session at Melwood Training Ground ahead of the UEFA Champions League Group E match against Sevilla FC. (Pic by David Rawcliffe/Propaganda)](http://thisisanfield.com/wp-content/uploads/P170912-037-Liverpool_Training-600x400.jpg)

Indeed, Klopp has the luxury of choice, and not just in terms of fielding strong benches. He has assembled a squad of sufficient adaptability that Liverpool ought to be able to capable of playing several systems.

He has waged war on specialists to such an extent that essentially one-position players, like Daniel Sturridge, may fear themselves an endangered species.

A core are genuinely versatile: imagine the descriptions Championship Manager would have had to use for not just Milner (D/M/F RLC?) Salah, Mane and Oxlade-Chamberlain, but also Emre Can, Philippe Coutinho, Adam Lallana, Gini Wijnaldum and Roberto Firmino, despite increasing evidence the last is at his best as a false, or genuine, No. 9.

Jordan Henderson and Joel Matip moved around their teams more in their younger days. Klopp has full-backs, in Alberto Moreno, Andrew Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold, with the pace and stamina to operate as one-man flanks, rendering them natural wing-backs.

The same may be said of Milner and Oxlade-Chamberlain, even if the latter moved from Arsenal in part because of a preference for a midfield role.

If such a shape requires a third centre-back and Liverpool could have benefited from buying another in the summer, Gareth Southgate seemed to suggest a solution.

He gave Joe Gomez his England debut in a back three, citing his assurance in possession as a reason for picking a defender who many a Liverpool fan would like to see relocated to a central area.

But Liverpool have been the anomalies among the top clubs. They have sat out the rush to copy Antonio Conte’s 3-4-2-1 formation that propelled Chelsea to the title.

They have the players to try it; indeed some of them featured, with Can in a back three, when Brendan Rodgers trialled it. A reason why they may not could be Klopp’s almost British fondness for a back four.

4-2-2-2

His 4-4-2 has the potential to be a Brazilian-style 4-2-2-2 or an isolated experiment. Coutinho and Lallana in particular are anti-4-4-2 players, men whose talents cannot be best accommodated in the rigidity of the old British system.

Equally, Klopp’s version of football is based less on fixed positions than likeminded players capable of occupying pockets of space and combining deftly. A formation is starting point, not a didactic description of players’ stations.

They revel in their unconventionality – the front three can be inverted when Firmino is in a deeper position than Mane and Salah – and a midfield trio with Coutinho on one side and a workhorse on the other could be both balanced and lopsided.

There is a case for saying that Liverpool have benefited from being proactive, from focusing on their own approach. They could set up with opposition in mind more often, but they prospered against the best teams by playing their own game.

Perhaps adding an element of unpredictability would make it harder to prepare teams to face Liverpool.

There is an argument that chopping and changing could detract from the understanding they have exhibited when playing 4-3-3. They are a team that rely on chemistry and altering the chemical equation could remove it.

But it did not when their diamond helped them beat West Ham 4-0 last season or their back-to-the-future 4-4-2 brought a 4-1 win this month.

Klopp’s phalanx of versatile players gives him myriad combinations. Choice can create problems when it confuses the decision-making, but he has permed the right ones twice against West Ham alone when he has deviated from the norm.

It should offer him encouragement to change more often.

Fan Comments