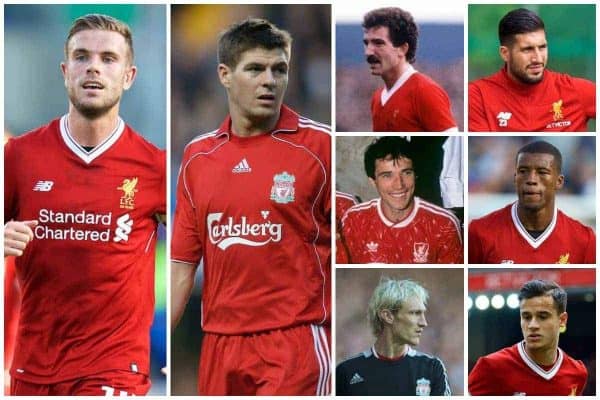

Ahead of the new season, Michael Holt assesses the changing role of the captain, and whether Jordan Henderson is the right candidate for Liverpool.

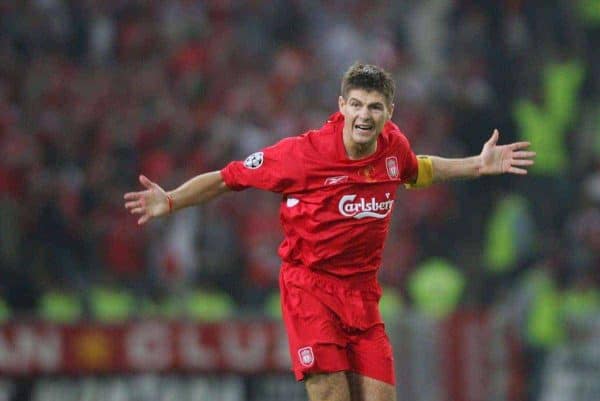

When Steven Gerrard moved to LA Galaxy in 2015, Liverpool lost one of its greatest, most influential players and its club captain. Replacing Gerrard was not an option: it is often inconceivable to replace a legend.

It was, however, the unenviable challenge afforded to Henderson when becoming captain, but does he remain Jurgen Klopp‘s best option?

While Klopp nor Liverpool have indicated change is afoot for the captaincy, it is worth discussing the requirements of the role and its shifting or evolving form through the years—what we’ve come to expect.

Henderson is a divisive figure among Liverpool fans with arguments for and against his role in the team.

It is, however, unquestionable that his injury in February coincided with our title challenge flat-lining; but was this due to the void in the holding midfield role or a lack of on-field leadership in his absence?

Henderson’s Performance as Captain

Arguably 2016/17 was Henderson’s best season in performance terms—even if he remains injury prone (making 17 and 24 appearances in the Premier League in the last two seasons), which often leaves a positional conundrum for Klopp to fill.

His place in the team is not necessarily aligned to his role as captain. If a captain is to lead on the pitch, to be the manager’s voice, then he must surely be present for a large part if not all of the season.

Henderson may have a decent range of passing and the ability to win the ball with energetic enthusiasm but he reflects what Gerrard was; Henderson is the Claude Makelele water carrier to Gerrard’s Francesco Totti dynamism.

Gerrard was an icon, a talismanic figure of inspiration to his city’s people. On the pitch, he led by example but wasn’t particularly tactically astute.

He was intuitive rather than calculating. If he’d been calculating, he may have been half the player he was.

Which other player could rasp through a tackle like Gerrard to rouse the Kop? Which other player could rifle it in the top corner almost without thinking?

Gerrard was the symbol of the city, the club, and its fans. Henderson should not be expected to emulate this, it’s futile.

But where Gerrard and Henderson meet is the fact their managers—Gerard Houllier and Brendan Rodgers, respectively—gave them the armband to mature a young talent, to thrust responsibility on young shoulders.

Sami Hyypia stood aside as captain to vice-captain in 2003 to elevate Steven Gerrard; to mature a 23-year-old with vast potential. It also ‘meant more to Gerrard’ as he was Liverpudlian.

What Makes a Captain?

In the traditional sense a captain is a vocal leader, an example to his team-mates and, often, a tactical brain to allow the team to function.

In contemporary football, the tactical foil has given way to an inspirational figure, an expressive or sometimes abrasive player.

Where once the dogged and resolute central defender commanded the team from the back, the central midfielder became the calculating figurehead driving the team forward.

There’s no definitive answer to what makes a captain but to travail through recent history can at least outline its possibly shifting nature and importance to a club, its fans and the team.

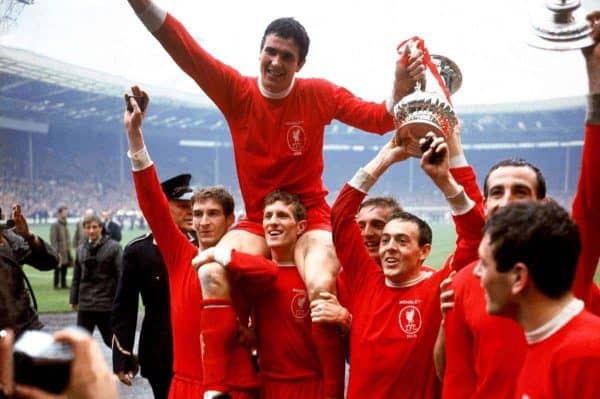

If you look at Liverpool captains from the Shankly period onward—aside from a Graeme Souness (1981-84) interlude—we have had the traditional skipper:

- Ron Yeats (1961-70)

- Tommy Smith (1970-73)

- Emlyn Hughes (1973-79)

- Phil Thompson (1979-81)

- Phil Neal (1984-85)

- Alan Hansen (1985-90, with Ronnie Whelan deputising)

- Mark Wright (1990-93)

These were different times: English football was far from the polished, cosmopolitan league it is now.

Into the Premier League era and you see a very different list of Liverpool captains, with centre-forward Ian Rush (1993-96) taking over from Wright in a marked switch.

But he was no leader and a fading force given his 31 goals in 98 league games, where once he netted 47 in a single season in 1983/84.

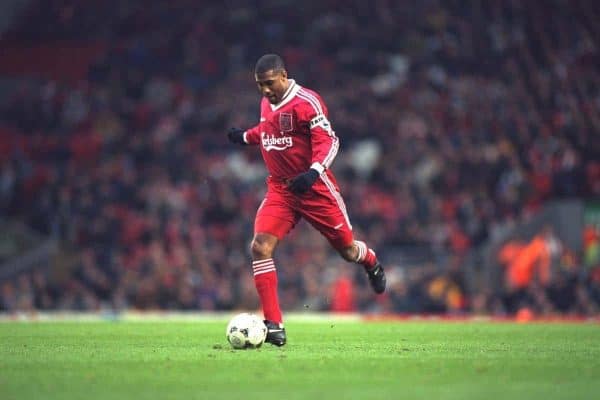

Following Rush’s departure to Leeds, it became about central midfielders as captain—a trend reflected in the Premier League more broadly—with John Barnes (1996-97), Paul Ince (1997-99) and Jamie Redknapp (1999-2002).

Of course, in Hyypia’s captaincy the club returned to the commanding centre-back presence (2000-03), only to switch back when Gerrard took the armband (2003-15).

In time, Liverpool went from towering centre-back captains to midfield generals, but the Premier League was not alone in this shift.

Attacking From the Back

From football’s beginnings, tactics have often been more style than shape. Changes to the offside rule in the 1920s led to a distinct move away from free-flowing attacking football, with forwards loaded in a 2-3-5 formation, to a “WM” setup.

Arsenal were the WM’s early adopters by creating a more rigid defensive unit with the centre-back at its core—the integral, pivotal point for the team. The game became more about defensive play than offensive.

In “Catenaccio” the defensive model deepened further with the introduction of man-marking and a sweeper, as deployed by Helenio Herrera’s 5-3-2 formation at Inter Milan with club captain Armando Picchi as sweeper.

From Picchi, to Franz Beckenbauer, Franco Baresi, Guiseppe Bergomi, Lothar Matthaus, to recently retired stalwarts Paulo Maldini, Carles Puyol and Javier Zanetti, this role of captain as defender is integral.

A seismic change came from Rinus Michels’ Total Football at Ajax, which sought to expose the limitations of man-marking as players held no fixed tactical position.

The emphasis was on flair, movement, and positional flexibility. A team would defend from the front and attack from the back. While Ajax and Barcelona captain Johan Cruyff is the iconic player of this style it should be noted he was a deep-lying forward.

And while teams tightened in proceeding years, the most recent tactical innovation was Barcelona’s “Tiki-Taka”, where Pep Guardiola’s men focused on ball retention and closing opponents down with Xavi Hernandez, Andres Iniesta or Lionel Messi the chief proponents.

Tiki-Taka sees a return to overloading attacking areas, deploying midfielders in full-back positions and zonally effecting play rather than exploiting space. The midfield general, Xavi, was arguably the most important figure in the team.

Albeit infinitely more defensive than the ball-playing Xavi, the deep-lying-midfielder-as-beating-heart can be seen in the captaincies of Makelele, Didier Deschamps and Roy Keane.

A current example would be N’Golo Kante at Chelsea: he is defensive and energetic, a throwback in many respects.

The examples show an evolution from a tactical presence at centre back, to the driving central midfielder, to the roaming deep-lying attacker.

As tactics evolve, will we see more attacking players used as captain purely for their inspirational moments? Is an attacking focal point necessarily a leader?

Mauro Icardi has moments of magic, but he’s no Matthaus; Lionel Messi can inspire, but he’s no Puyol.

What to Expect From a Captain

If previously the captain was one of organisational and positional strength as centre-back, it has moved further forward in recent years.

But disconcertingly it may move entirely into the realms of symbolic gesture: a token to fans or to the player.

Whether it is to give the captaincy to ‘one of us’ (Harry Kane at Tottenham, for example) so to give the fans a figure to hang their collective hat; or, to keep a player at a club to entice them into an ego-filled “world-saver” role.

Either way it devalues what ‘captain’ represents: the manager on the field.

It could be argued that John Terry was a great captain, leading the team, galvanising them at key moments, and was also a Londoner, appeasing fans in a cosmopolitan age.

Another symbolic figure with substance was Francesco Totti at Roma, replaced by the equally talismanic Daniele de Rossi.

It could be said that in Chelsea’s attempt to replace Terry they have resorted to replicating Terry, in affording the captaincy to Gary Cahill—a commanding English centre-back who throws his head in where it hurts.

It’s captain-by-default, a token captaincy as a symbolic gesture of camaraderie. Cahill is an empty vessel, symbolic of a departing club legend.

Captain Antihero

To return to Liverpool, based on a shifting nature of tactics, could it be argued that Liverpool missed the opportunity for a great captain in not giving the job to Xabi Alonso?

While Gerrard was a figurehead, a Scouser, was he the most notable leader? Granted, Istanbul is an obvious standout moment, but what role did Rafa Benitez play in rallying the troops at half-time?

Instead of the hero figure, the “world-saver”, maybe modern football would prefer an antihero pulling the strings. A Xabi Alonso: not a focal point but the puppet master, the unsung hero.

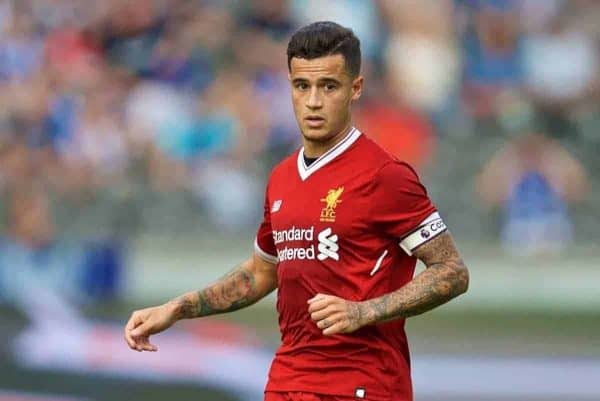

In a similar rationale, would Liverpool give the captaincy to our playmaker Philippe Coutinho but in a bid just to keep him? Would it be a calculation to make him feel like he’s the figurehead, more valued than simply an understudy to Messi or Luis Suarez?

Or, should Klopp be happy with Henderson driving the team forward?

Or, would Liverpool’s defensive unit benefit from the introduction of a central defender captain in Joel Matip? A traditional captain who sticks his head in to clattering boots, a leader by example.

Does It Matter Who is Captain?

Is there then a case for not replacing Gerrard with one captain but a string of captains?

Should the sound responsibility rest on the spine of the team—‘divisional captains’—in Matip, Henderson, Can and Coutinho, for instance?

In a side that needs certain players to take on responsibility, maybe we should force their hand and make them take on the role. It is, after all, a role that demands maturity on and off the pitch.

Or is there a leftfield example for Klopp to consider, one maybe not necessarily immediate in the mind. One in the mould of the quiet achiever of Alonso: a role model who could dictate the pace?

A player who is technically astute with and without the ball, tactically aware in a deep-lying berth, energetic as a box-to-box midfielder who often surges diagonally upfield into inside-right positions, a high-pressing player.

No, it’s not Emre Can, it’s Georginio Wijnaldum.

Should the Dutchman be used in a midfield consisting of Can in a defensive foil to the advancing Coutinho, Liverpool would have the necessary bite and flair to be combative in the forthcoming season.

Wijnaldum could dictate the tempo, retain the ball, close opponents quickly, open up the pitch and compact the play when needed. A contemporary footballer steeped in tactical evolution.

The surprising case for Gini Wijnaldum, Liverpool captain?

* This is a guest article for This Is Anfield. If you’d like to contribute a piece for consideration please see here.

Fan Comments